The current exhibition aims to view Abdi’s creative work from a more personal, private point of view, combined with an inquiry of his strong desire and sensitivity to material qualities which is impressively present through his work.

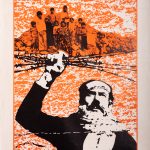

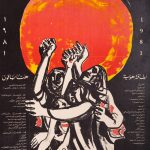

Abed Abdi (b. 1942, Haifa) is a Palestinian-Israeli artist educated as a graphic designer in the former DDR,1 then the earlier part of Abdi’s career was dedicated to the graphic arts, mostly printing, as he served as the graphic designer for Al-Itihad 2, the bi-weekly publication of Al-Itihad association. Nonetheless, Abdi’s creative force has spanned over 50 years and multidisciplinary media – from etching to murals, from monumental sculpture to small-scale oil paintings.

Beyond his extensive work in diverse media, Abdi’s iconography marks a long contribution to the Palestinian struggle for recognition and the voicing of Palestinian particular identity, history and suffering as a central theme of his creative work.

These two aspects are presented through different works throughout his artistic career, however, in the current exhibition we have chosen to concentrate on three important bodies of work, enriched by an extra selection of other projects which we refer to as “footnotes”, namely, their position and presence in the project is directed to enlighten the central themes and topics revealed through Abdi’s work.

Materials

Abdi’s two-dimensional and relief work engages with different materials taken from the long history of art, building materials, and culturally charged objects.

The art materials include gesso, graphite, charcoal, oil pastels, pastel crayons, water, acrylic and oil paints, carbon copy paper and printing materials. Beyond conventional painting materials, Abdi’s work also contains varied substances taken from hardware and building materials: sand, straw, ceramic paste, ropes, jute sacks, wires, netting, tin and copper. The specificity of culturally charged objects is presented through the inclusion of glass marbles, wooden beads, carpets, embroidery panels, assorted fabric sheets, paper talismans, copper plates, candlesticks, clocks, calendar, dolls, measuring tape, keffiyah fabric, photographs, and UNRWA printed sacks, etc.

| |

|

|

| Fig. 1

Abed Abdi, Fabric shed in space, 2011 Plastic netting, porcelain glue, ropes and acrylic on canvass 80X90cm |

Fig. 2

Abed Abdi, Tent, 2011 Plastic pipe, jute, porcelain glue, ropes and acrylic on canvass 95X60cm. |

Fig. 3

Abed Abdi, Bird’s eye-view over a shed in Al Arkib, unrecognized village, 2011 Gesso and acrylic on canvass 70X85cm. |

This collection of materials that combines together the worlds of art, building and Palestinian culture is the fundamental layer of Abdi’s art. He carefully chooses his materials, each choice clearly loaded with references before even becoming part of his imagery, hence becoming a charged substance into which Abdi›s emotions and ideas are stylized. Once this collection is in his hands, Abdi displays his images and narratives to create the complex tableaux of his art.

Tents, Fabrics, Sheets: Folds and Strings

the fold to infinity 3

Abdi’s images contain various themes that recur in a spiral manner. This spiraling is best demonstrated through his interest in working with actual cloth and representations of fabric. These may be in the actuality of folded fabric as reshaped planes (fig. 6), or the play between the paper’s flat, smooth surface, and the uneven surface of the folded, sometimes twisted, and wrinkled fabric placed upon it (fig. 4).

A selection of Abdi’s fabrics reveals that many of these are taken from the specific image of tent side walls or eaves, sometimes with the actual use of woven carpets or embroidered sections. Some of these are described as merely laid upon the earth, creating a second, loose layer that covers or represents the soil beneath (fig. 4).

In other cases, complex geometrical structures are presented from a bird’s eye view on the top of a tent’s upper side (figs. 1-3).

|

|

| Fig. 4

Abed Abdi, Tent wall/ Fabric, 1987 Graphite on paper 68X84cm. |

Fig. 5

Abed Abdi, The flying tent, 1994 Graphite, watercolors and acrylic on paper |

The selection of images display Abdi’s constant interest in the tattered tent, the floating fabric, the temporality and deconstructed nature of these structures. Abdi’s floating tents and overviews of the fabric structures echo Gottfried Semper’s theories on the fundamental relations between fabric and structure, textile and architecture.4

In Semper’s view, the folding of fabric, the passage from the flatness of the sheet to the three-dimensionality of the tent, is the source of architecture.

Abdi, on the other hand, is interested in the remains, in the partial, the leftovers of the fragile structure of the tent; hence, the fabrics become the metonymy of fragility and instability. Abdi’s are fragmented, broken, floating, drifting sheets that exist as particles, as remains or debris, as a reminder of the temporality and the flux of nomadic and refugee life, or the denied, deported, or extradited. The feeble, nomadic reminiscences go beyond the romantic Bedouin nomad to signify the refugee — a person who does not have a fixed place or land, a structured home or autonomy over life and statehood. The refugee, the prisoner, the resident of an unrecognized village that has been destroyed by the authorities time and again is the nomad that occupies Abdi’s paintings.

|

|

|

| Fig. 6

Abed Abdi Praying carpet and jute sack, 2011 Jute, porcelain glue, ropes and acrylic on canvass 100X80cm. |

Fig. 7

Abed Abdi Jute folds, 2011 Jute fabric, sand, porcelain glue, ropes and acrylic on canvass 100X80cm. |

Fig. 8

Abed Abdi Knitted sheet, 2012 acrylic on paper 70X60cm. |

Deleuze provides an important reference to the disposition of the nomad, the one who passes through smooth space, unregulated by the rules and structures of the striated space. 5

For Deleuze, the nomad is the only possible critic of modern, ordered lives, where all sorts of nomads — from schizophrenics to guerrilla fighters — transgress the rigid limitations of hegemonic rule. In this spirit, any definition of Palestinian identities from the point of view of the Israeli government includes this dichotomy of regime and order vs. the nomad, the infiltrator, the terrorist, the guerrilla fighter, the unlawfully stayed (shabah), detained prisoners and so forth. Abdi’s fabrics signify this instability of existence and presence, while his portraits embody these identities and their presence vis-à-vis the viewer in the gallery.

The fold is a complex structure that denies a simple dichotomy between inside and outside. It functions as ‘doubling’, and allows embracing or withholding the appropriated, delivering it inside (figs. 6-7). Therefore, the particular shape of the fold in the jute sack, and the presence of the decorated prayer carpet within, reshapes the understanding of Abdis complex relations to the Palestinian issue. A successful Palestinian artist, living in Israel, enjoying the benefits (and difficulties) of Israeli citizenship, Abdi also deeply identifies with the fate of his close and distant family, as well as the position of other Palestinians, whose fate has turned to the dark and suffering side.

The folding of the two-dimensional flat fabrics that are marked with varying signifiers of Palestinian identity, indicate the complexity of Abdi’s position as an insider, yet outsider, one that belongs yet is watching from the relative safety of his contemporary life. The red line cutting across the length of the folded sack fabric is an indication of the larger sack, the pride in being able to deliver larger quantities of flour and other foodstuffs for the benefit of the family. It becomes an indicator throughout Abdi’s work – as lengthy red lines, a reference to these sacks, cut through his varying images (fig. 2 and 6). Fabrics, therefore, are an important, specific signifier of Palestinian identity on the one hand, yet they also indicate criticism of and disobedience to hegemonic rule, preferring the position of the nomad over that of the ruling power.

Image within an image

Abdi’s images reside between material factuality and representations. At times, his work interestingly marries both practices into an intriguing continuity, one that holds together the material factuality of the fabric with the symbolic quality of representation, as an appropriation of an image in a painting. The following group resides within the amalgamation of portraiture and fabric, serving as a midpoint between the fabrics (the tent wall, the veil or the sack), and the idea of the portrait as elaborated below.

|

|

| Fig. 9

Abed Abdi Woman sleeping in a tent, 2002 Gesso and acrylic on paper 70X87cm. |

Fig. 10

Abed Abdi Woman from the Boulata Refugee Camp, Nablus, 1993 Watercolour and acrylic on paper 64X55 cm. |

Woman Sleeping in a Tent (fig. 9) and Woman from the Blata Refugee Camp, Nablus (fig. 10) exemplify this concept. Both make use of fabrics to cover and conceal their presence. One is holding a tent’s wall to cover herself when sleeping, while the other is concealed in a veil set against another square that blocks the background and visual context, an image that alludes to the separation wall between Israel and the West Bank. The way the tent wraps the body and how the fabric is folded around the woman’s face is the approach into the territory of nomads, whether Bedouin in tents on their routine wandering around the desert, or the refugee as nomad — she who has lost her dwelling and is in the limbo of impermanence and uncertainty about the present or future.

|

|

| Fig. 11

Abed Abdi Veronica of Palestine (image of Grandfather Nayef al-Haj), 2012. Fabric, Gesso and acrylic paint on paper, 71X77cm. |

Fig. 12

Domenico Fetti (1588–1623) Veil of Veronica, 1618. oil on panel, National Gallery, Washington DC |

In the context of human figure and fabric, Abdi draws a specific allusion to the Christian tradition of St. Veronica.6 Such is the image of Veronica of Palestine (image of Grandfather Nayef al-Haj) (fig. 11), in which the old man’s portrait floats over an image of veiled women weeping behind barbed wire. Saint Veronica is the Christian name of the woman of Jerusalem who wiped the face of Christ with a veil while he was on his way to Calvary.

According to tradition, the cloth was imprinted with the image of Christ’s face. A comparison to Domenico Fetti’s image (fig. 12) reveals the similarities of this sorrowful and painful experience. While for St. Veronica the absorption of Jesus’ sweat and eventually his facial impression created a holy moment of faith and trust, Abdi’s image is a moment of passion and suffering, impressed through the image of the old man, literally attached to the weeping women›s anguish.

A similar composition, of a woman holding a man’s portrait image, is Abdi’s The Demonstrator (fig. 13). The image, presenting a young woman holding a man’s (photographic) image, is a direct reference to a common Palestinian practice by the wives, mothers’ and children of imprisoned men in Israeli jails, seeking a way to communicate the absence of the beloved and the family’s suffering. The practice of preparing a significant, well-staged studio photographic image of young men is a fascinating signifier of the Palestinian struggle.7 Many men desiring to take part in the fighting for Palestinian independence are likely to be caught and held by Israeli authorities, while others may meet an untimely death through struggle. Therefore, the images are prepared with the future of prison or death in mind, and as such are mementos, souvenirs, or keepsakes. As if to paraphrase Roland Barthes’ idea of the presence of death in the photograph8, Abdi’s employment of these prints is a reminiscence of death, deportation, exile and banishment inflicted upon these people. The smiling faces, the optimistic photograph is an image of a lost past that is not to be revived soon.

Moreover, a close examination of Abdi’s image (Fig. 13) reveals that the woman holding the frame is also gently framed with two lines, indicating the similar fate shared by Palestinian men and women alike.

|

|

| Fig. 13

Abed Abdi The Demonstrator, 1985 Charcoal on paper 100X70cm. |

Fig. 14

Palestinian woman holding photo of her father who is in Israeli jail. Raphah Today, Daily Life in Palestine |

Portraits: The Unrecognized and the Intimate

Abdi’s portraits on display are a collection of images that bring forward the possibility to portray, name and give identity to those denied of such basic rights by the authorities. In Abdi’s work, Fatima abu Shursh, illegal stayer (fig. 15), A woman from an unrecognized village in the Negev (fig. 16), and A woman from the Balata refugee camp, Nablus (fig. 17) are all real people of body and flesh, of face and name.

Nonetheless, the exhibition displays a series of those denied presence or identity, side by side with those most familiar — Abdi’s mother, father, sister Lutfiyah, cousins and other members of the extended family. Abdi offers an embrace to those who are personally unknown to him, yet he shares their pain and grievous fate, accepting them within his extended family, nation and story. Abdi’s narrative is a sequence of inclusions, of understanding the linked destinies of those rejected and abandoned by the regime, denied by the hegemonic discourse, neglected to their fate.

| |

|

|

| Fig. 16

Abed Abdi Fatma Abu-Shursh, Unlawful Stayer, 2012 85X60 cm. Silkscreen and acrylic on paper |

Fig. 17

Abed Abdi A woman from an unrecognized village in the Negev, 2011 Watercolor and acrylic on paper |

Fig. 15

Abed Abdi In the confinement cell, 1986 Monotype and printing paints on paper, 70X50 cm. |

Abdi’s use of photography within the context of his family is also significant. While the authorities relate to Palestinians under titles and labels such as “unlawful stayer”, “detainee”, or “member of a terrorist organization” etc., the indexical, specific quality of the photograph as an image stating itself to be “that which has been”, marks the presence of the photographed as a persona of face and name. Abdi collected photographic images from his own album, images taken in Haifa studios, as well as images of his sister Lutfiyah (sent from Damascus in 1967) and of his aunts in Amman. He then merged the photographs with the fabric, either the woven carpet, the embroidery fabric and the talismans of Abdi’s mother’s images, or with the canvas fabric with the clear reference to the UNRWA flour sacks, the jute panels of Abdi’s memories of life in refugee camp. Interestingly, Abdi uses stitching with needle and thread to attach the photos to their canvas backgrounds, creating complex relations between representation and craft, materiality and image.

In his hands, the collection of fabrics (including the photograph printed on canvas), is the arena of competing feelings of suppression and repression, where materials stand as a metonymy of human fate, their tactile tangibility and textural qualities being central to their meaning.

Coda

The final two panels recently prepared for the exhibition are dedicated to Deeb Alalu, a Palestinian refugee living near Damascus (fig. 24), and Lutfia, Abdi’s sister who is a Palestinian refugee, still living in Yarmouk Camp at the outskirts of Damascus (fig. 25).

panels recently prepared for the exhibition are dedicated to Deeb Alalu, a Palestinian refugee living near Damascus (fig. 24), and Lutfia, Abdi’s sister who is a Palestinian refugee, still living in Yarmouk Camp at the outskirts of Damascus (fig. 25).

In his image of Lutfia, Abdi has conglomerated the varying layers of knowledge and representation of this show into one final piece: the substance of the painting is made like a tent wall, using pierced tarpaulin which is attached to the wall with ropes; the photographic image marks Lutfia’s “Being there”, the indexical mark 10 of her actual presence, the person who she is, Abdi’s sister, and her absence from Haifa in general, and Abdi’s life in particular, for the past 67 years. Lutfia also stands between the intimate, family portrait, and simultaneously, she performs the notion of “refugee” or an “absentee”, according to the legal terminology.

The painting itself uses references to past works with the usage of jute fabric, caffiyah fabric, and a three-dimensional object that signifies a package, a bundle, in reference to the person who runs away at times of danger, trying to collect as much as possible of personal belongings and precious objects.

| Fig. 26 Deeb Allu, a Palestinian refugee in Bagdad, 2013 Photograph, beads, keffiyeh, ropes and amulet on tarpaulin stretched with ropes 300X70 cm |

Fig. 27 My Sister, Lutfiyah, 2013 Photograph, jute sack and acrylic on tarpaulin stretched with ropes 300X70 cm |

She is also endowed with decorative woven fabric and personal talismans for protection. All in all, Lutfia’s image serves as a pivotal point of indication and a cross reference to the majority of works presented at Abdi’s solo show.

Abdi has not given up on his elderly and ailing sister, although he cannot see her or meet her. Hence, his most personal story, becomes the metonymy of the Palestinian state of affairs, of past, present and future.

By Dr. Ayelet Zohar

Haifa Feb. 2013

Notes:

1 Abdi attended the Graphic Design and Mural Art departments at the Fine Art Academy in Dresden between 1964-1971.

2 Il-Itihad used to be a bi-weekly magazine published by Al-Itihad association and the Israeli Communist Party magazine, published since. Abdi was the graphic designer of the magazine between 1971-81.

3 Gilles Deleuze (2001, c1988), The Fold , Tom Conley (trans.), London: Continuum, 140. Tents, fabrics, sheets: Folds and Strings The Fold to infinity Gilles Deleuze3

4Gottfried Semper ( c1851). ‘The four elements of Architecture: a contribution to the comparative study of architecture’ and ‘The Textile Art: Considering in itself and in relation to architecture’, in: the passage from the flatness of the sheet to the three-dimensionality of the tent, is the source of architecture.

Harry Francis Mallgrave & Wolfgang Herrmann (trans.) The four elements of Architecture and Other Writings (1989) Cambridge: , 74-129 and 215-263, respectively.

5 Gilles Deleuze & Felix Guattari (1980). ‘1440: The Smooth and the Striated’, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 474-7.

8 Roland Barthes (2000. c1980). Camera Lucida, London: Vintage, 13-5, 31-2, 90-2, 97.

8. Wigodar, Meir (2002). ‘Shahid Cocktail: Reflections on the Fracture of Everyday Life’, Studio 134 (June-July 2002), 14-23, 18-20. 9 See: Bailey, David A. & Gilane Tawadros (eds.)(2003).Veil: Veiling, Representation and Contemporary Art, exh. cat, Iniva in association with Modern Art Oxford.

10 On the Index, see: Barthes, .10-1

Dr. Ayelet Zohar is the curator of Abed Abdi’s exhibition titled “Homage to Lutfia, My Sister in Yarmouk Camp – Paintings and Two-Dimensional Work”. The exhibition is open until the 31st of August 2013 at Beit Hagefen Gallery in Haifa.

| Ayelet Zohar is an artist, independent curator, and visual culture researcher, specializing in the study of photography and contemporary arts in East- Asia.

Recently, Zohar curated an homage exhibition to Nam June Paik at the University of Haifa (2013); Smashing!: Fragments and Deconstruction in Contemporary [Ceramic] Arts for the Benyamini Centre of Contemporary Ceramics in Tel Aviv (2012), raising questions concerning the presence of ceramics in the contemporary art field. In 2005 Zohar curated the exhibition PostGender: Gender, Sexuality and Performativity in Contemporary Japanese Art, Tikotin Museum of Japanese Art, addressing questions of sexual identity and gender characteristics in the work of Japan’s leading photographers and video artists. In the current exhibition, Zohar curated Abed Abdi’s work considering the wider context of Palestinian art in Israel, and the tension between the desire for personal-private creation, and the sense of urgency to contribute towards the collective struggle for the identity and status of Palestinian culture in Israel today. Zohar views the curatorial process as a new medium – an expansion of the language of installation art. In her academic research Zohar published a text on the pictorial language of Ibrahim Nubani, camouflage and invisibility; Zohar also researches the work of Hannah Farah, and its connection to the Kufur Bir’im tragedy in the context of architecture, archaeology and the archive.

|