Palestinian art created within Israel’s 1948 borders possesses unique characteristics deriving from its being part of the visual culture of the Palestinian minority in Israel. In this artistic-national construct, the artist, graphic designer and printmaker Abed Abdi played a leading role as a consequence of his work over the decade between 1972 and 1982 as graphics editor of the publications of the Communist and Democratic Front for Peace and Equality parties, the Arabic language journal Al-Ittihad and the Al-Jadid literary journal. Additionally, many of his works were also published in the Communist Party’s Hebrew language paper, Zu Haderekh (This Is the Way) and in a variety of election and other posters for the Communist Party and the Democratic Front. The fact that Abdi often reused images he created in various contexts also reinforced the iconic status of many of his works.

The present article will focus on two subjects that play a significant role in shaping the visual culture and collective memory of the Palestinian minority in Israel. First, “the art of print”, a term I employ to define the presentational space and practice of works of art printed in relatively large editions in the press, books, booklets, posters and postcards. Although these works are often accompanied by political, journalistic, literary and poetical texts, they are not illustrations per se but rather visual texts that are often of equal status to verbal ones. By means of this space and practice, the reproduced works gradually establish the visual culture of their target audience. Hence, they are an autonomous alternative presentational space and practice of works of art that played a most important role in shaping the national culture of all sections of the Palestinian people.

The second subject is the planning and erection of the “Land Day” monument in Sakhnin in 1976-1978, and its attendant preliminary sketches done together with the artist Gershon Knispel.1 This monument, which is identified as one of the turning points in the Palestinian presence in the public arena inside Israel, became a particularly significant and influential factor in everything pertaining to the formation of the national collective memory in general, and the visual memory in particular, of the Palestinian minority in Israel.

1. The Trailblazer: Abed Abdi

Biographical Milestones

Abed Abdi was born in 1942 in the church quarter of downtown Haifa. In April 1948, he, his mother, his brothers and sisters were uprooted from their home, while his father remained in Haifa. From Haifa the mother and her children traveled to Acre from where, two weeks later, they sailed on a decrepit boat to Lebanon. In Lebanon they were first housed in the “quarantine” transit camp in Beirut port, and later moved to the Miya Miya refugee camp near Sidon, from where they continued to Damascus. After three years of wandering between refugee camps, the mother and her children were allowed back into Israel as part of the family reunification program.

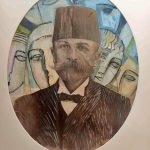

In his youth Abdi joined the Communist Youth Alliance in Haifa, where he also began his artistic journey. In this environment he was first exposed to Social Realism and Israeli artists who adopted this style and who, at the time, were close to the Israeli socialist-communist Left. In 1962 Abdi was accepted for membership in the Haifa Association of Painters and Sculptors, becoming its first Arab member, and also held his first exhibition in Tel Aviv. In 1964 he was sent by the Haifa branch of the Israeli Communist Party to study graphic design, mural art, environmental sculpture and art in Dresden in the German Democratic Republic. Abdi lived in Germany for seven years, completed his masters degree in arts and a year of specialization. At the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts graphics and printing department he met the woman who was to become his teacher and most important source of inspiration, the Jewish artist Lea Grundig, who had gained a reputation for her protest works against fascism and Nazism. During those years Abdi was also influenced by German artists such as Gerhard Kattner and Gerhard Holbeck.

He returned to Haifa in 1971, and in November 1972, the city awarded Abdi the Herman Struck Prize2 and to mark the occasion he held an exhibition of his works at the city’s Beit Hageffen Gallery. In 1973 the works shown in this exhibition were printed and published in a portfolio, and in the following years some of them were also published on occasion in Al-Ittihad, Al-Jadid, and in poster form. In the 1970s and 80s he also did illustrations for the texts of Palestinian and Israeli writers and poets. In 1978, two years after the Land Day events in Sakhnin, together with Gershon Knispel he created and erected the monument commemorating Land Day. Later, Abdi also created monuments in Shfaram, Kafr Kana and Kafr Manda.

Over the years Abdi worked as an art teacher in Kafr Yasif, and since 1985 has served as an art lecturer at the Arab College of Education in Haifa. During the years he served as the graphic editor of Al-Ittihad and Al-Jadid (1972-1982), many of his illustrations appeared in those papers, in journals and books, and also in numerous political posters including those marking Land Day, posters marking the Kafr Qassem massacre, and Israeli Communist Party election posters.

Dresden, the Formative Period: Artistic-Ideological Influences

Clearly identifiable in Abdi’s works from the seven years he spent in Dresden, are traces of a consistent artistic and subject matter trend that focused on figures of refugees and were done in a Social Realism style using artistic graphic means such as drawings, stone prints and etchings accompanied by political and literary texts dealing with justice and morality. To a great extent this trend was influenced by the sociopolitical worldview adopted by Abdi in his youth when he joined the Communist Party, but it was also mediated by the artists of the Social Realism school in Israeli art. These trends, however, matured in Dresden, inspired by the works of two women artists: the printmaker, painter and sculptress Käthe Kollwitz and painter and print artist Lea Grundig.

Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945) devoted her work to creating empathic descriptions of universal suffering resulting from a life experience of distress, exploitation and discrimination, and from revolutionary or traumatic historical events, and she had firsthand knowledge of a life of suffering, poverty and hunger: after her marriage to Dr, Karl Kollwitz (1891) the couple moved to a poor neighborhood in Berlin and it was this environment that provided her with the materials that fortified her political consciousness and nourished her work until her death.3 Her most famous works include the “Weavers’ Revolt” cycle (1893-1897), which is based on a play by Gerhardt Hauptmann that describes the Silesian weavers’ revolt in 1844; the “Peasant War” cycle (1901-1908) that is dedicated to the peasants’ revolt in southern Germany in the second half of the 16th century; the “Grieving Parents” memorial (1914-1932); and the numerous leaflets she designed for Internationale Arbeitshilfe (IAH) from 1920 onward. In the Weimar Republic Kollwitz enjoyed canonical status and her works were studied and disseminated throughout Germany. Following the Nazis’ rise to power, Kollwitz was forced to resign from the Academy of Fine Arts, her works were declared “decadent art” and were removed from public exhibitions. She spent most of the war years in Berlin but in 1943 was evacuated to Dresden where she died on 22 April 1945, two weeks before Nazi Germany’s capitulation.

Abed Abdi was well acquainted with Kollwitz’s work before he left for Germany. In the 1950s they had been printed in Israel in art journals such as Mifgash, and communist newspapers like Kol Ha’am, Zu Haderekh and Al-Ittihad. Abdi’s friends and colleagues, such as Ruth Schluss, Yohanan Simon, Moshe Gat and Gershon Knispel, all diligently studied Kollwitz’s work.4 Her drawings, prints and etchings influenced generations of socio-politically conscious artists sensitive to human suffering both inside and outside Germany.

Whereas Abdi became acquainted with Kollwitz’s work mainly through reproductions, the influence of Lea Grundig on his work was more direct. Grundig had known Käthe Kollwitz, and in many respects continued her tradition into the 1960s. But in addition to underscoring the suffering of the working class, Grundig’s work was marked by the horrors of World War II, and the iconography she created focuses on issues such as refugeeism, expulsion, survivors and so forth, issues that in the twentieth century had become identified with that war. The profound influence of Grundig’s works is clearly evident in Abdi’s development as an artist during his studies and in the iconographic shaping of refugeeism in general, and the Nakba iconography in particular, in his work.

Lea Grundig (née Langer) was born in Dresden in 1906 and died during a trip to the Mediterranean countries in 1977.She studied with Otto Dix at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts, married the painter Hans Grundig, and the two became active members of the German Communist Party (KPD) in Dresden. Following the Nazis’ rise to power, Lea and Hans Grunding were persecuted, detained for questioning, and were even arrested on several occasions. In 1939, a short time before her husband was sent to a concentration camp, Lea finally left Germany and reached Palestine aboard the refugee vessel, the S.S. Patria, in 1940. In 1944 she exhibited her “Valley of the Dead” cycle (1943) that directly addressed the events of the Holocaust: refugeeism, expulsion, freight wagons, executions, concentration camps, and so forth. The Israeli artistic establishment was unsympathetic towards “Valley of the Dead” and Lea Grundig, who was in Palestine during World War II, had difficulty in understanding how the country’s Jewish artists could ignore the Holocaust.5

Following her husband’s liberation from the camps, in 1947 Grunding joined him in Soviet-occupied Dresden, which in 1949 became part of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), where she became an important and respected artist and lecturer at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts, whereas in Israel she was almost completely forgotten.

The encounter between Abed Abdi, a twenty-two year-old Palestinian recently arrived from Israel, and Lea Grundig, his teacher at the print and etching department at the Dresden Academy, was of great significance for him.6 Their relationship went far beyond the usual student-teacher format; Grundig opened her home to him and was his social and cultural mentor for most of the time he spent in the GDR.

It is, however, important to emphasize that this somewhat surprising encounter between a young Arab victim of the Nakba and the Jewish Holocaust survivor Lea Grundig was marked by their political and experiential common denominator, their commitment to social and political justice, their protest against war and the heavy toll it exacts from humankind. It was not, therefore, influence derived from a Jewish cultural or historical context, but rather one of a communist cultural and philosophical context. It was actually their communist, cosmopolitical and a-national identity that enabled their encounter and friendship, and their great mutual admiration.

Palestinian Art in the Palestinian Diaspora, the West Bank and Gaza Strip

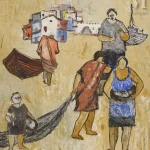

One of the most prominent characteristics seen in a perfunctory review of the various branches of Palestinian art is the important role played by printing as a vehicle for disseminating the messages that this art seeks to advance. In the context of the art of print, clearly evident is the influence of Ismail Shammout (1930-2006), one of the first Palestinian artists. After his expulsion from Lod in 1948, Shammout reached a Gaza refugee camp after a long and arduous journey through Jordan, and in 1956 moved on to Beirut. He left Beirut for Kuwait after the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, spent several years in Germany, and died in Amman in 2006. Shammout’s life embodies the ordeal of the Palestinian odyssey. Moreover, since he defined himself first as a Palestinian and a political man, and only second as an artist,7 Shammout took upon himself the mission of a witness whose role it was to tell the world and its future generations the story of his people through art. He served as the first head of the PLO’s Art Education Department immediately after the organization was founded in 1964, and his book Art in Palestine (Kuwait, 1989) was the first publication on Palestinian art and its history. For these and other reasons the role he played was of particular importance for both the establishment of the field of Palestinian art and the formulation of modes of representation of the Nakba, which were also disseminated in the works of other artists in the Palestinian diaspora, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip from the 1950s to Shammout’s death in 2006. Furthermore, many of his works were reproduced and widely disseminated in posters, postcards and calendars. Shammout’s influence on Abdi’s work is of particular importance in all matters regarding the image of Palestinian refugees.

Abdi attests to the mutual influence and reciprocal artistic relations in the 1970s and 80s with Palestinian artists of his own generation from the West Bank and the Gaza Strip who acquired their education at art schools in the Arab world (mainly in Cairo, Alexandria and Baghdad), among whom are Nabil Anani (b. 1943, Emmaus), Taysir Barakat (b. 1959, in a Gaza refugee camp), Ibrahim Saba (b. 1941, Ramla), Issam Bader (b. 1948, Hebron), Vera Tamari (b. 1945, Jerusalem), Tahani Skeik (b. 1955, Gaza), Taleb Dweik (b. 1952, Jerusalem), Kamal Moghani (b. 1944, Gaza), Fathi Gaben (b. 1947, Gaza), and others. The most notable is Suleiman Mansour (b. 1947, Bir Zeit) who, in contrast with the abovementioned group, studied at the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem for one year (1969-1970). Abdi also became very familiar with the work of artists active in the Palestinian diaspora who engaged in the pure symbolism of “Palestinian suffering”. Among the notable refugee camp artists are Naji al-Ali (b. 1936 in the Galilee and grew up in a Lebanese refugee camp) who worked in Lebanon and London,8 Ibrahim Hazima (b. 1933 in Acre and grew up in Latakia, Syria) who won an art scholarship in East Germany and later continued to work in Europe, Tamam al-Akhal (b. 1935, Jaffa) who studied art in Alexandria and Cairo, married Ismail Shammout and worked in Beirut from where she moved to Jordan, and Kamal Boullata (b. 1942, Jerusalem) who studied art in Rome and Washington and on completing his studies in 1968 remained in the United States where he wrote the history of Palestinian art in a large number of books, catalogues and articles.

In the context of Palestinian art in Israel it is worthy of note that as a result of the Palestinian Nakba and life under military government, Palestinian artists became active within Israel’s borders only at a relatively late stage, some 25 years after the establishment of the State of Israel. The military government period imposed harsh isolation on those artists who remained within Israel’s borders. The imposition of military government on the majority of Arab residential areas by virtue of British Mandate emergency laws was intended to restrict, as it indeed did, the freedom of expression, movement and organization of the Arab citizens. It was therefore only after military government was revoked in 1966 that young Palestinians began to study art in Israel and abroad. After Abdi’s return to Israel, in the 1970s and 80s the artists Assad Izi (b. 1955, Shfaram), Ibrahim Nobany (b. 1961, Acre), Assim Abu-Shaqra (b. 1961, Umm el-Fahm), and Osama Saeed (b. 1957, Nahef) went to study art, and their work reflects the unique culture of the Palestinian minority in Israel.9

Social Realism in Israel

Before his departure for Germany and on his return Abdi worked together with others identified as “Social Realism” artists in Israel who in the 1950s and 60s came together in “Red” Haifa, the ethnically mixed city with its large workers population.10 These artists engaged in every facet of Israeli reality out of a profound identification with its deprived and discriminated against sections. They sought to create art with social messages that would be understood by and be accessible to “the masses”, and thus they created artistic prints that were both affordable and which conveyed their message. Gershon Knispel was the driving force behind the Haifa Social Realism artists’ circle, whose ranks included Alex Levi and Shmuel Hilsberg, and maintained contact with artists who created in this style and resided in other locations in Israel, such as Avraham Ofek, Ruth Schluss, Shimon Zabar and Naftali Bezem.

Commitment to this global idea and worldview is also clearly evident in Abdi’s words at a panel discussion11 held in 1973 by the Haifa Association of Painters and Sculptors at Chagall House, under the title “Artists in the Wake of Events”:

In the same way that an artist lives the events of the past, present and future, he also lives the conflict between Man and the forces of evil and destruction. And when society and humankind are in crisis, the artist is required to express himself harmoniously by means of the artistic vehicle at his disposal […] and so […] the role of the artist in his work, thoughts and worldview is to reinforce the perpetual connection between himself and the society in which he lives. I was brought up according to this approach and thus I understand the connection between my artistic work and the role defined by Kokoschka, who sought to remove the mask for all those who want to see reality as it is. The role of fine art is to show them the truth (A. Niv, Zu Haderekh, 13.2.1974).

Speaking about his art and the 1973 War, Abdi said:

Out of my worldview and my loathing of war, and also out of my profound concern for the future of relations between the two peoples, Arab and Jewish, I have shown my two works here in the exhibition [entitled “Echoes of the Times” in which artists from Haifa and the north of Israel participated]. When the cannons thundered on the Golan [Heights] and the banks of the [Suez] Canal, and when the future of the region was at risk, I recalled the words of Pablo Picasso and in my work I said “no to war” in accordance with my artistic beliefs; art must be committed and play a role (ibid.)

2. The Refugee Print Portfolio

In the years Abdi spent in Germany (1964-1971) he created a most impressive corpus of illustrations, lithographs and etchings mainly dedicated to either the Nakba or the Palestinian refugees. A group of the refugee works which Abdi created in Germany between 1968 and 1971, and which was published in 1973 as a set of twelve black and white prints entitled “Abed Abdi – Paintings”, offers a glimpse of central motifs that would later recur in many of his works. In these and other works, clearly evident is the mark left by his childhood experiences when he moved between refugee camps, and from the period following his family’s reunification in Haifa. To depict the refugees Abdi adopted a Social Realism approach of the kind to which he was exposed prior to his departure for Germany, and which he refined while he was there.

All the figures in the print portfolio are of refugees. In the pen and ink drawing, “The Messiah Rises” (no. 1), no. 10 in the portfolio, the figure of a barefooted, elderly, tall, bearded man is seen walking alone, behind it tumbledown huts or houses with sloping roofs, and around its head are allusive rays. In another work from the same period that is not included in the portfolio, “Refugee in a Tent” (no. 2), the loneliness of the refugee is again emphasized. The etching presents a close-up of a bearded, wrinkled face, a sad mouth and eyes, and a kind of headdress that seems like a tent. In contrast with the loneliness of the elderly refugee in the two previous works, Abdi places him in a social context in print no. 4 of the portfolio, the lithograph “Revelation of the New Messiah” (no. 2). Here Abdi depicts a human wave on whose crest is a man borne on the shoulders of the people. The figures of the anonymous refugees are drawn in filament-like lines that create a single body-mass-wave. United in one fate, barefooted, they are shrouded in long robes. The man borne on their shoulders seems to emerge from within them and his long arms are spread wide in either a blessing or an attempt to maintain his balance. The entire mass of figures is surrounded by a void, similar to the figures in other works in the portfolio (and similar to many of Kollwitz’s works). The religious context of a redeeming messiah is somewhat surprising in the work of a communist, Social Realism artist. But this messiah is a man of the people, a man who has nothing, the chosen one who comes from the people, spreads out his arms/protection over them, the man who is to lead them to a better future. Compared with Ismail Shammout’s famous 1953 painting “Where To?” (no. 4), in which the frightened refugee looks forward along the road he treads in a barren geographical expanse, the refugee messiah in Abdi’s work is looking with pride at the observer from the height of his elevated position. Compared with another of Shammout’s works too, the 1954 “We Shall Return” (no. 5), the proud figure of the refugee in Abdi’s work, drawn in bold black lines, conveys resolve, not helplessness or fear.

However, Abdi too addressed the helplessness of the Palestinians and emphasizes it in print no. 8, the charcoal drawing “Refugees in the Desert” (no. 6). In this drawing the refugees are seen from afar as a human swarm, similar to the way in which Grundig presented her refugees, but with Abdi they do not fill the entire “frame” and it is impossible to discern their expressions. In his expressive drawing the hundreds of unidentifiable refugees create a meandering road that vanishes into the hills close to the horizon. High above the refugees stands the burning sun that is drawn in several bold lines in a completely cloudless sky.

In the context of landlessness and loss of familial identity, the feminine presence is particularly emphasized. In print no. 2, a pen and ink drawing of dense lines, “Women” (no. 7), two women are seen, their heads covered, curled up in their long dresses/cloaks, as they sit withdrawn into themselves facing one another. The face of the woman sitting on the right of the drawing looks directly at the observer with a sad and worried expression. Except for a low horizon and the same burning sun, here too the background is devoid of character and the women appear to be floating in the space of the paper.

Another picture of a woman refugee appears in print no. 1 of the portfolio, the pen and ink drawing “Weeping Woman” (no. 8) in which in a close-up of her face tears can be seen in her eyes in a composition reminiscent of Käthe Kollwitz’s “The Widow” (1922-23) (no. 9).

The sense of tragedy and loneliness is expressed differently in print no. 8, the pen and ink drawing “Sleeping in the Desert” (no. 10), in which two figures, a child and his mother, are seen sleeping alone on the ground under the sky. The figures are covered with a sheet whose folds resemble a sharp and desolate landscape reminiscent of the landscapes in the portfolio. The real landscape in the drawing is summarized in a few broken lines marking the horizon, and several electric poles and wires. Mother and child are extremely and dramatically foreshortened. Despite the change of orientation from the heads downward and not from the legs, this foreshortening calls to mind the work of one of the first artists to employ this technique, the Italian Renaissance artist Andrea Mantegna, “The Lamentation over the Dead Christ” (circa 1480). To intensify the dramatic effect Abdi exposed one of the mother’s feet, which peeps from under the sheet, and this touching exposure of part of her body underscores the harsh conditions of sleeping on the ground.

The last two prints in the portfolio are landscapes. The landscapes painted by Abdi in Germany are characterized by a return to lengthened black lines and an atmosphere of expressive tempest. In print no. 11, the pen and ink drawing “The Dam”, waves are seen breaking against a high rampart with towering turrets, the silhouettes of minuscule figures on a high dam and a black sun drawn in dark circular lines like a coil of wire. In print no. 12, the pen and ink drawing “Wild Landscape”, what appear to be rocks or tree stumps are seen, a kind of path wending its way through a black and depressing landscape, clouds drawn in expressive black lines, and a black sun. It is a landscape of consciousness, a black landscape of scorched earth. In the absence of people and signs of life, it seems that this earth represents a post-traumatic experience or a landscape in the aftermath of a terrible catastrophe, after the Nakba. It is another means of concretizing the atmosphere of the tragedy, the storm, and the struggle that imbues all the works in the portfolio.

In a critique of the print portfolio that appeared in Zu Haderekh, A. Niv (the pseudonym of poet Moshe Barzilai) noted the connection between Abdi’s works and those of Käthe Kollwitz, and said that the works in the album speak in “a clear language of non-acceptance of Palestinian fate […] The album is a single totality despite the differences between its subjects. For the subject is but one: identification with the fate of the refugees, non-acceptance of this fate, and an expression of hope and emotional turmoil” (A, Niv, 11 July 1973).

The prints in the portfolio were also reproduced in the Mifgash journal and Zu Haderekh, together with cultural articles and Hebrew poetry and literary texts (“Sleeping in the Desert”, for example, was reproduced in Zu Haderekh on 15 November 1972, and print no. 1 of the portfolio, the pen and ink drawing “Weeping Woman” was reproduced in the same paper on 11 July 1973). The presence of these drawings and prints in the bi-national cultural system of the Israeli Communist Party was of great significance, and thanks to it they were preserved in the memory of the readers of these journals as the ultimate representation of the Nakba.

3. “Mandelbaum Gate” and “The Pessoptimist” by Emile Habibi

From time to time during his years in Germany, Abdi visited his hometown, Haifa. It was on these visits that he became acquainted with several notable Palestinian writers and poets. During these years and later, many of his drawings illustrated the publications of writers such as Emile Habibi, Anton Shammas, Taha Muhammad Ali, Salman Natour, Samih al-Qasim, and others. In this context Abdi’s figures on white paper draw their local, concrete force from the textual literary space. From this standpoint his work is marked by the tremendous textual influence of Arabic literature, poetry and spoken language on Palestinian art in general, by means of what Kamal Boullata terms “the hidden connotations of words”.12

In his relationships with writers and poets, of particular note is the relationship Abdi formed with Emile Habibi,13 who like him was a native of Haifa. The fruitful collaboration between them was given expression, inter alia, in a 1968 illustration by Abdi for Habibi’s story “Mandelbaum Gate”14 (no. 13) done prior to his return to Israel. Once a year, at Christmas, the Mandelbaum Gate, the only crossing point between the two parts of pre-1967 Jerusalem, was opened for Christian residents of Israel to visit their families in Jordanian refugee camps. The gate symbolized both the division of Jerusalem and that of the Palestinian people following the 1948 Nakba.15

In his illustration for “Mandelbaum Gate” Abdi depicts the parting of a wrinkled woman leaning on a cane, and a girl-child with unkempt hair standing behind her with head bowed by the barbwire fence. The girl’s heavy shadow follows the woman, takes her right hand and returns like an echo on the shape of the cane she is leaning on, held in her left hand. The figures are standing in a setting in which only the vital details are drawn in an empty space – barbwire fences and two tall posts with an allusive barrier between them. Abdi turns our gaze towards the no-man’s-land at Mandelbaum Gate. Balas describes Habibi’s writing as “consciousness of the torn homeland” and the no-man’s-land as symbolizing a dual schism of “those forced to live outside their land hoping to return to it, and those living detached from the majority of their people and hoping to be reunified with them”.16

Following Abdi’s return to Israel he created illustrations for the original Arabic edition of Emile Habibi’s The Pessoptimist: The Secret Life of Saeed Abu el-Nahs al-Motashel, published in 1977.17 The one that opens the book (no. 14) is a close-up of a man’s face partly concealed by his hand that is seemingly signaling the observer-reader to halt – “No further”. The hand does not enable identification of the face, but seemingly invites the observer to read the man’s future in its lines. In this way Abdi depicts Habibi, a product of Israeli reality and the complex identity of the Palestinian minority living in it, which conducts a complex dialogue with its environment as it holds its cards close to its chest.

In another illustration (no.15), which appears on the book’s frontispiece, a gaunt, bearded old man is seen whose face is furrowed and whose eyes are sunken. He is wearing a galabiya whose stripes/folds are heavily marked. His big left hand rests on his chest and his right hand hangs at his side. Within the background scribbles that partly appear to be an abstract representation of Arabic script, planted beside his head is a barred aperture alluding to a prison or solitary confinement cell. The story describes, inter alia, the imprisonment of Saeed Abu el-Nahs al-Motashel in an Israeli jail and his ironic/cynical responses to the Israeli interrogator’s questions, whereas Abdi’s illustration conveys sorrow and exhaustion and is devoid of any form of irony.

An oppressive and melancholy atmosphere also pervades the drawing (no.15) that appears facing p. 193 in the chapter entitled “More than Death Is Hard on Life, this Story Is Hard to Believe”. In the illustration the partly-covered lower torso of a corpse is seen lying on a wooden surface with its feet visible. Behind the improvised stretcher stand grieving women dressed in the hijab, and in front of it stands a man with his back to the observer, and who is turning his face away from the body at his feet.18 A tear can be seen in the corner of the man’s eye.

In a scene from Habibi’s book, Walaa’s parents, Saeed (the narrator) and Baqiyya, are making their way to Tantura to save their son, and their story is related in the following chapters until the son and mother mysteriously vanish into the sea. Habibi’s ironic and allegorical text ridicules the efforts of the Israeli security forces as they chase shadows. But this gloomy drawing of Abdi’s chooses to ignore the text’s irony and instead depicts the parents’ terrible grief for their dead son.

The tension between the text’s ironic tone and the dark, expressive drawings is present in each collaboration between Abdi and Habibi. Abdi translates Habibi’s multifaceted irony into simple and accessible language, and focuses on the tragedy of the Palestinian people. But the “consciousness of the torn homeland” described by Habibi ably qualifies the entire gamut of Abdi’s work which is populated by Palestinian villagers and city dwellers together with refugees and displaced persons. Yet this “consciousness” also aspires to universal justice and equality, and is expressed in a universal artistic language that crosses national borders and identities.

The epitome of explicit reference to the Nakba in Abed Abdi’s work is a series of his illustrations for the collection of short stories by Salman Natour “Wa Ma Nasina” (We Have Not Forgotten). The stories were first published in 1980-1982 in Al-Jadid, and later as part of a trilogy by the author.20 In the magazine, the title of each story appears within or next to an illustration by Abdi. The names of the stories are: So We Don’t Forget, So We Shall Struggle, Introduction by Dr. Emil Tuma; A Beating Town in the Heart; “Discothèque” In the Mosque of Ein Hod; Om Al-Zinat is Looking for the Shoshari; “Hadatha” Who Listens, Who Knows?; Hosha and Al-Kasayer; Standing at the Hawthorn in Jalama; A Night at Illut; “Like this Cactus” in Eilabun; Death Road from al-Birwa to Majd al-Kurum; Trap in Khobbeizeh; The Swamp… in Marj Ibn Amer; What is Left of Haifa; The Notebook; Being Small at Al-Ain… Growing Up in Lod; From the Well to the Mosque of Ramla; Three Faces of a City Called Jaffa.

The names of the stories reflect a remapping of Mandatory Palestine, the lost Palestine, resembling that which was carried out by the historian Walid Khalidi in his book All That Remains.21

Unlike the format of the short stories published in Al-Jadid, in which a different illustration by Abdi accompanied each story, only two were chosen for Salman Natour’s book, which reflect the space of Palestinian memory, comprising a combination of abstract and concrete elements. The cover of the book features detail from an illustration originally made for story Being Small at Al-Ain… Growing Up in Lod.22 The original illustration depicts three refugee women – one of whom is sitting and tenderly embracing or protecting a baby, and behind her two monumental figures completely covered in their heavy robes, against a backdrop of a round sun and a strip of obscure buildings. In the detail featured on the cover of the book the image has been cut and all that remains are a section of the seated figure and a section of the figure standing to the left, her head bowed towards the figure sitting at her feet. We Have Not Forgotten, states the title, and the original version of the illustration, and especially the detail, indicates an abstract consciousness of memory that is not located in a concrete geographic space.

The second illustration was originally published as part of the story What Is Left of Haifa”23, and it is a detailed illustration of the city of Haifa. This story relates to a specific place and time, Haifa and 22 April 1948, the date of the expulsion from the city, and thus both the story and the illustration are anchored in time and place as a biographical, personal and collective milestone in the history of the Palestinian residents of Haifa.

This illustration is reproduced and recurs beside the title of every short story in this book and thus becomes a kind of “logo”, linking Abdi’s personal biography as a native of Haifa with a symbolic sequence of wandering: from Haifa to Lod, from Haifa to Ramle, from Haifa to Jaffa, etc. A space of geographic memory, place names, details of streets, businesses and the names of people along the continuum of the Palestinian Nakba.

This illustration is “The Father Illustration”, one that to a great extent contains the essence of the Nakba iconography developed by Abdi over the years. It is designed as a triptych: in the left-hand section a large number of figures are sketched as black patches, becoming a human swarm that seeks to leave from the Port of Haifa in haste and congestion; in the central part there is the figure of the father, Qassem Abdi, with a simple worker’s hat on his head, and behind him the “Kharat Al-Kanais” (church neighborhood), with its churches, mosque and clock tower, as well as the family home. In the right-hand section there is a graphic sketch of the ruins of the Old City of Haifa.

Natour relates in his story:

The wrinkled sheikh walks hand in hand with the years of this century […] When the Nakba is mentioned he says: “I was 48” and adds, “I witnessed it on the day their cannons were on the tower, and they dropped a yellow sulfur bomb on the Jarini mosque clock, and the clock fell, and I said: the clock has fallen and the homeland will follow.”

Haifa was not erased from the face of the homeland […] but all its characteristics have changed […] The people of the Old City of Haifa were mostly stonecutters and fishermen […] They quarried the stones in Wadi Rushmia and sold them, and later, when the British came and extended the harbor, people started to work there as well […] Rifa’t was a skilled fisherman like no other, he had a black donkey which he used to ride and look out to sea, and see where the fish gather, then he would cast his net, and not miss even a single fish.

Time passed, and the sea began to bring people and take people away. And Abu Zeid’s boats took the Arabs away…

Where to? To Acre Port…

Where to? To Beirut Port…

Where To? To hell…”( Natour, 1982)24

To a certain extent Salman Natour’s story about Haifa is based on the stories of Abdi’s family. Thus, for instance, Rif’at the fisherman is Abdi’s great-uncle. The detailed story of the family appears in the book written by Deeb Abdi (Abed Abdi’s brother), Thoughts of Time, which was published posthumously in 1993. In the book, short stories he had written and which had been published over the years in Al-Ittihad were collected, including the story of the family’s grandfather and his departure from Haifa in April 1948. The illustration on the cover (no. 19) is also related to the departure from Haifa.25 The images in this illustration are arranged in a composition of a cross, so that the horizontal line is formed from the houses of Haifa, sketched in black and outlined by the waterline of the Port of Haifa, while the vertical line is formed of a fishing boat, with heavily outlined figures on it in black lines. The three figures in the foreground are in detail: the figure of a woman holding a kind of package close to her body, the figure of an older man and beside him, the figure of a young child holding on to him. Deeb Abdi relates:

This is what our leaving Haifa for Acre on board British boats was like […] In April, the sea was stormy, which is unusual at that time of the year, and the high tide almost took us to the deep waters, deeper and deeper to the bottom of the sea. My grandfather Abed el-Rahim was standing upright as if he were challenging the waves and other things; he was looking back at Haifa, as if they were saying goodbye to each other. For the first time he was leaving Haifa, and she was leaving him, and she faded away bit by bit, and my grandfather Abed el-Rahim watched the length of the shore from Haifa to Acre, the wheels of a horse-drawn wagon bogging down in the moist sand.

A short journey, then we go back. That is what my grandfather Abed el-Rahim said when I was still a little boy, hardly eight, and I was afraid of the dark, of the sea. For the first time in my life I was sailing to an unknown world – unknown. From the big mill they were shooting bullets like heavy rain, and my grandmother Fatma el-Qala’awi hid us in her lap, continuously reciting the Throne Verse from the Qur’an and we did not dare raise our heads. So we remained where we were until we were far from the shore and reached the deep sea, and approached Acre. We stayed in Acre for a couple of weeks, its walls were suffocated by refugees, and the refugees were suffocated by crowds of immigrants who had escaped by land and sea to its walls. A short time afterwards, Acre fell, and people left it by land and sea.

We went on board at night and sailed deep into a world foreign to Haifa and Acre. It was the beginning of a journey… and another journey… and another (Deeb Abdi, 1991).26

The narrator, a child who is afraid of the dark and the sea, is waiting for a savior to save him from his misery. The expectation of a savior to rescue him from drowning is familiar to Abdi from his mother’s stories about El-Khader. This character appears in Salman Natour’s story What Is Left of Haifa in which a group of people is visiting Elijah’s (El-Khader’s) cave. They drink and eat, and when they go into the sea somewhat tipsy they begin to drown. “The old people began to pray: Please, Khader, save us, Khader”, writes Natour, and suddenly they saw a man in a boat in the sea, but he disappeared like a grain of salt. And of course nobody drowned.

This savior-messiah figure of El-Khader, as the Prophet Elijah, as Mar Gerais, recurs in many of Abdi’s illustrations, two of which appear in the 1973 print portfolio. Six years later, in an illustration from 1979 (no. 20) the savior reappears as a manneristic figure, the folds of whose garment is reminiscent of those of the saints in Byzantine icons. It flies with arms outstretched over a village, but all it can offer the refugees is consolation, not real protection and rescue; it is a mythological, religious and community figure detached from its land and the source of its power.

In contrast, the old and wrinkled sheikh, the narrator of all Natour’s Wa Ma Nasina stories, who also appears in the majority of the illustrations that accompanied these stories in Al-Jadid, represents a man of flesh and blood. However, there is a tension between the text, in which the sheikh is the narrator who remembers in detail all the events of the Nakba (names of people, dates and places), and the universality of the illustration, as it is manifested in the archetypical face of the old man and the faces of the other figures in the illustration series.

Thus, for example, the illustration that accompanies the story From the Well to the Mosque of Ramla,27 (no. 21) incorporates heavy religious allusions with real suffering. The old man with his deeply furrowed face appears here as if crucified in sacrifice or as protecting the figures of the wailing women standing behind him with a dead, shrouded body lying beside them on wooden boards. Here, Natour’s narrator relates the story of the bomb that exploded in the middle of Ramla’s Wednesday market in March 1948, killing many. He describes the ensuing chaos and the numerous bodies lying among the market stalls and crates of fruit and vegetables. The incorporation of the religious image into the scene of mourning against the background of a few buildings, and the schematic depiction of a mosque’s minaret charges the event with timeless and placeless symbolism. Despite the highlighted word “Ramla” in stylistic script that appears within the background architecture, the body lying with its face hidden is simultaneously a specific and universal victim.

In other illustrations, the dialectical tension between detailed text and symbolic illustration recurs. An example of this is the illustration that accompanies the story Like this Cactus in Eilabun28 (no.22). It depicts a corpse lying on the ground at the foot of a bare tree, and the figure of a woman who is touching the body’s face with a hesitant hand. Behind them, several women are sitting covering their faces in shock. The figures are situated in a desolate space, far from the village that is seen on the horizon, and far from any source of help. The story opens with a long scene in which Natour describes the dirt road leading to Eilabun, the surrounding fields and mountains, and the tension between a young Palestinian woman and her children and an Israeli soldier who is with them on a truck traveling from Eilabun to Tiberias. Later, the narrator relates the story of the massacre in Eilabun, the death of Azar, a poor man, the children’s favorite, who was killed while leaning against the church door, and the death of Sama’an al-Shufani, the janitor of the Maronite church, whose body lay on the ground for three days.

In Trap in Khobbeizeh29 the wrinkled old sheikh tells the story of a shepherd trapped in a minefield near Khobbeizeh in Wadi `Ara, the total destruction of the village, its inhabitants’ struggle to return to their lands after they were declared a closed military zone, and the trial of one of the villagers for trespassing. He goes on to describe the massacre in Khobbeizeh in which 25 men were taken from the village, forced to kneel beside a cactus hedge, and were shot to death in full view of the women and children. The narrator dwells on the story of one of the victims, the only son of Abou Daoud Abou Siakh, who begged the soldiers to let him take his son’s place. The soldiers denied his request and shot his son, the father loses his mind, and for years afterward sees his dead son’s face among the village children.

The three figures accompanying the story do not describe the killing and horror, but the stunned expression of the villagers watching the atrocity. On the story’s frontispiece (no. 23) a group of grieving women with their heads covered is seen, one of whom is bending her head to a small child clinging to her waist. In this work Abdi returns to the circle motif, which here is seen as if through a magnifying glass or as a close-up of the faces of the weeping, wailing women. Seen in the narrow and elongated illustration that appears with the story, are upright, grave-faced men with big, wide eyes and big, emphasized hands (no. 24). The third illustration (no. 25), a lateral woodcut printed on the lower part of the two columns of page 25, presents grief-stricken figures standing behind barbwire and wooden fence posts.

The Story of a Monument

The first Land Day took place on 30 March 1976 in protest against the government’s decision to expropriate 20,000 dunams (approx. 5,000 acres) of land in the Sakhnin area for the purpose of “Judaizing” the Galilee. The leaders of the Israeli Communist Party and the heads of the Arab councils in the Galilee called for a day of general strike and protest demonstrations on 30 March. The demonstrations were held mainly in Sakhnin, Arabeh and Deir Hanna, in the course of which IDF forces clashed with the demonstrators, many of whom were wounded and six were killed.

In the mid-1970s the struggle intensified, as did the discourse conducted by the Arab minority in Israel since 1948 on the lands and their expropriation. Abeb Abdi first addressed this subject in a poster he designed for a national conference on protection of the lands that took place on Saturday, 17 October 1975 in a Nazareth cinema. This event’s slogan was “Save What Remains Of The Lands, Fight Against Expropriation So We Do Not Lose What Is Left” (no. 26). The dramatic design of the text in red and white on a black background was done in the best tradition of socialist posters. At its center, printed in a thin white frame is an adapted version of a 1971 woodcut presenting a group of people raising their clenched fists. The united group that seemingly bursts out of the woodcut’s left edge and fills some three quarters of the surface, moves to the right against a background of abstract broken lines (the original work was published in Al-Ittihad on 7 October 1971). In the poster, Abdi ascribes the people’s protest to the land issue by putting agricultural tools – scythes and hoes – in the hands of some of them, which did not appear in the original work.

In 1977, a year after the Land Day events, the secretariat of the National Committee for the Defense of Arab Lands, headed by Saliba Khamis, decided to erect a monument commemorating Land Day and its victims.30 The meeting at which the decision was taken was held in the home of Kafr Manda council leader Muhammad Zeidan, and it was taken in consultation with the then head of the Sakhnin council Jamal Taraba. At the meeting it was also decided to approach Abed Abdi and ask him to take the task upon himself.

Once the committee had approached Abdi, he invited his old friend Gershon Knispel,31 who had considerable experience in monument design, to participate in the project. The two formulated the monument’s ideological-visual format and began work on the preliminary sketches, four of which are included in the monument portfolio (nos. 27-30) that was published in 1978, after the monument was erected.32

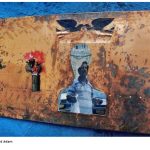

Several months after they were approached, on 30 March 1977, the anniversary of Land Day, the two presented a model of the monument to a well attended gathering of the Galilee Arab Councils Committee (no. 31). The model (90 X 60 X 30 cm) is comprised of two separate elements: a kind of sarcophagus made up of panels of aluminum reliefs presenting a narrative continuum that moves from images of women tilling the soil of the homeland to grieving women, and finally to bodies. There is also a free sculpture of a plow set on a separate pedestal (no. 32).

In the last week of March 1978, work on construction of the monument commenced in the Sakhnin cemetery on the assumption that this would protect it from harm, since the Israeli security forces would avoid entering the site. First, the concrete base was cast (nos. 33-36). This took several hours and was done by numerous workmen from Sakhnin. In the course of the work the police arrested Sakhnin council head Jamal Taraba on a charge of authorizing illegal construction, but released him several hours later.33

The unveiling ceremony was held on Thursday, 30 March 1978, and since then, every year on that date the monument is the center of the Land Day memorial ceremonies in the Galilee. On the one hand, the ceremonies reflect the seminal place of Land Day in Palestinian national culture, while on the other they serve as a platform for the various political, social and cultural struggles engendered by every period. From a historical standpoint, 1976 marked only one decade from the end of the military government period. However, as it transpired, the end of military government did not mark the end of what might be termed the “internal occupation and oppression” of the Arab population of Israel, or the discrimination against it. Yet Land Day became the first public event in which conditions matured for creating a permanent mark in the public arena in the form of a place for gathering, mourning, commemoration and remembrance. It became a “memorial site” in the full sense of the term coined by Pierre Nora.34 It is a site intended to remind the public and individuals of the events of the past, to mark meanings for them, and offer them a source of dynamic legitimacy. As a “memorial site” it also continues to live in the ceremonies held there every year and in the photographs and news items documenting it35 (nos. 37-39).

Description of the Monument

Knispel and Abdi designed a kind of four-sided sarcophagus covered with aluminum reliefs highlighting the connection of the Arab minority with its land (no. 40). The aluminum reliefs were fashioned in a way that endows them with the appearance of clay.

On the first panel (no. 41) a woman is bending and clutching a large jug, and two other women stooping, one harvesting with a sickle and the other sowing seeds. Beneath their arms, in the bottom right-hand corner, is an inscription in English, Arabic and Hebrew: “Designed by A. Abdi and G. Knispel to deepen understanding between the two peoples”; on the second panel (no. 42) a sculpted woman is bending, holding seeds in her left hand and scattering them with her right.36 It continues with a separate panel in which, between the woman and the edge of the image beginning on the side, inscribed in Hebrew and English are the words: “30.3.1976, In Memory of Those Who Fell on Land Day”. On the third panel (no. 43), sculpted successively in profile are two grieving women kneeling and covering their faces with their hands.37 Between the two women is an inscription in Arabic: “They fell so we could live. They live. The fallen of the day of defense of the land, 30 March 1976”, and beneath it are inscribed the names of those killed and their villages: Khair Muhammad Yassin of Arabeh, Raja Hassin Abu-Ria, Khader Abed Khaleileh, and Khadija Shawhana of Sakhnin, Muhammad Yusuf Taha of Kafr Kana, and Rif’at Zuheiri of Nur Shams, who was shot in Taibeh. On the left edge of this panel, towards which the women are facing, an abstract embryonic figure seemingly bursts from within the panel stretching its hand forward in a gesture of either grasping or a plea for help. The fourth panel (no. 44) completes the sarcophagus image by presenting two figures that seem to be corpses lying one on top of the other in a lateral, serene composition. The work on this panel is very reminiscent of Soviet memorial art. Finally, separate from this part of the monument stands a free sculpture of a plow on its own pedestal: when the tillers of the soil are murdered, the plow remains abandoned and broken (no. 45). The plow’s handles and axle are sculpted at a 45° angle, and from a certain viewpoint appear to be hands raised in supplication to heaven. In this sculpture there is special emphasis on the sense of molded clay that endows it with an organic appearance of patina and antiquity.

In general terms it may be stated that women are presented in most parts of the monument as working the land and symbolizing mourning and lamentation. The choice of focusing on figures of women was a joint decision by the monument’s two creators, who devote a central place to women’s figures in their other works. In any event, this choice runs counter to the period’s newspapers’ focus on the figure of the male peasant (see, for example, no. 46), albeit it connects with the perception of the woman as “Mother Earth” in both Arabic and modern literature, and also in Palestinian art.38 However, Abdi’s and Knispel’s women tillers of the soil are completely different from the village women’s figures derived from this perception in the art of Ismail Shammout, for example. Their representation highlights their being “proletarian”, diligent and dedicated working women, not ideal, idyllic allegorical figures.

The overall impression evoked by the two parts of the monument is one of a meld of the local, the specific and the universal. In addition to the element of commemoration and underscoring the Jewish-Arab cooperation that the Israeli Communist Party inscribed on its escutcheon, the monument represents not only a Social Realism approach, but also a Socialist Realism one. The joint work of Abed Abdi and Gershon Knispel highlights both connection to the land and a call for universal justice. This emphasis is also expressed in the texts written especially for the monument portfolio by Samih al-Qasim and Joshua Sobol, and those written by the artists themselves.

In his text, Abdi wrote:

Generations come and go and each one leaves behind it monuments whose existence continues in the present. These remnants sadden me, a sadness that comes to me from within the uprightness of the palm tree, the depth of the cactus’s roots, from the height of a derelict mosque, or a rusty church bell that will peal no longer. I feel the wounds of the continuum of the not too distant past and its suffering: the rocky surfaces of the bastion’s stone walls lay strewn before the bulldozers of “progress”, and I have tasted its saltiness which is similar to that beading a dark-skinned forehead. The same sweat that bitterness-laden history has turned into heavy tears falling onto the gravestones that have become monuments in the villages of Sakhnin, Kafr Qassem, Tantura and Deir Yassin. The monument we have erected in Sakhnin will be a witness and oath to our eternal belonging to this land and its prayer, and to its sons who answer the call to defend their motherland.39

Together with the Arabic texts by Abdi and Knispel the portfolio contains detail of Gideon Gitai’s photographs: a mother, her head covered and wearing a flowered village dress holding a baby, surrounded by the rest of her children amid the ruins of their demolished house (no 47). From a visual standpoint this image is also very reminiscent of scenes of destruction of homes in refugee camps, and thus visually links the fate of the Arabs of 1948 with that of their brethren outside Israel. Hence, for Abdi’s part the monument in Sakhnin is a way station along the continuum of “gravestones that have become monuments in the villages of Sakhnin, Kafr Qassem, Tantura and Deir Yassin”, a continuum reflecting the continuing Palestinian Nakba through the sweat and tears of its victims.

This photograph appeared in 1980 in a popular poster designed by Abdi to mark the fourth anniversary of Land Day. In the poster, the slogan of the struggle that focuses on saving “what is left” was replaced with the challenge “Here We Stay!” (no.48). In the lower part of the poster there is a photograph of a man raising his hand that is grasping a bundle of cut barbwire. Above the upper piece of wire is embedded a photograph of a woman surrounded by her children standing amid the ruins of their home.

The caption of the poster is identical to the tile of Tawfik Ziad’s poem “Hunna Bakun”40, which says, inter alia: “Here on your hearts we shall stay as a bastion. In hunger, naked, we shall challenge”.41 The repetition of the poem’s title and the allusion to its content is not random, since the poem is considered to be one of the most important expressions of resistance literature written by the Arabs of 1948. Moreover, the poem and its title are directly connected with collective Palestinian memory by unequivocally expressing the notion of summud (steadfastness) and the deep connection to the soil of the homeland despite the Nakba and what followed it.

Afterword

In 2008 Abed Abdi became the first Arab artist living in Israel to win the Minister of Science, Culture and Sport Award, together with six other artists, all of whom were Jews and younger than him. In other words, he was the first Arab artist to gain recognition by mainstream Israeli culture. Replying to a question from an interviewer regarding the excitement generated by the event in the Israeli media, Abdi said, “If I really am the first Arab artist, it is neither a compliment to me nor to 60 years of the State of Israel”.42 Indeed, it seems that thus Abdi faithfully summed up the attitude of both the state and the Israeli art establishment towards Palestinian art inside the Green Line. Abdi, the prolific and groundbreaking artist in so many respects in the sphere of Palestinian art, was forced to wait until he was sixty-six to gain this recognition.

This important artist, whose great work was compared by the award’s panel of judges to that of Nahum Gutman, has devoted himself for close to fifty years to a wide range of artistic endeavor in varied fields: painting, murals, illustration, prints, sculpture, graphic design and monument design. However, I have chosen to focus on two expressions of his multifaceted work – “the art of print” and the Land Day monument at Sakhnin. This choice was based on the degree of exposure to the broad Palestinian public and its role as a “memorial site” and a sort of “Palestinian museum”, and of course, their contribution to the development of the Nakba theme, depictions of refugees, and the struggle for the land in the national collective memory of the Arab minority living in Israel.

Notes:

1 The Sakhnin monument stood at the center of the “The Story of a Monument: Land Day in Sakhnin” exhibition (curator, Tal Ben-Zvi). For further reading on the exhibition see, Gish, Amit, “You Will Build and We Shall Destroy: Art as a Rescue Excavation”, Sedek 2, 2008, pp. 117-119, the exhibition website: www.hagar-gallery.com, and the exhibition catalogue: Tal Ben-Zvi, Shadi Halilieh, Jafar Farah (eds.), 2008, Land Day: The History, Struggle and Monument, Mossawa Center, Haifa [Arabic].

2 A. Niv noted the Hebrew dailies’ ignoring Abdi being awarded the prize: “The first Arab artist to win the prize in his homeland, the Herman Struck Prize” (A. Niv, 11 July 1973).

4 Balas, Gila, 1998. “The Artists and Their Works”, Social Realism in the 1950s, Haifa Museum of Art, pp. 15-32.

5 Amishai-Maisels, Ziva, 1993. Depiction and Interpretation: The Influence of the Holocaust on the Visual Arts, Oxford, Pergamon Press, p. 382.

6 In one of my conversations with him, the artist noted that his relationship with Lea Grundig was founded on the sensitivity she displayed towards war and injustice, and inter alia due to her belonging to the Jewish minority that had suffered so greatly during the Nazi era (conversation with Abed Abdi, 19 March 2007).

7 See Paula Stern, “Portrait of the Artist (Palestinian) as a Political Man” at http://www.aliciapatterson.org/APF0001970/Stern/Stern11/Stern11.html

8 Naji al-Ali worked as an illustrator for newspapers in Lebanon and the Gulf States between 1957 and 1983. In 1983, when walking to his newspaper’s London office, he was wounded in a drive-by shooting and died a month later. The Intifada in the West Bank broke out that same month.

11 In addition to Abdi, also participating in this panel were the artists Avshalom Okashi and Gershon Knispel, art critic Zvi Raphael and architect Haim Tibon.

12 Boullata, Kamal, 1990. “Israeli and Palestinian Artists: Facing the Forest”, Kav 10: 171 (Hebrew).

13 Emile Habibi (1921-1996), author, publicist, and one of the founders of the Israeli Communist Party, which he represented in several Knessets. He was also editor of Al-Ittihad for 45 years.

14 Abdi’s illustration appears in Emile Habibi, Sudaseyyat el-ayyam el-setta (The Six-Day Sextet), Haifa, Al-Ittihad, 1970.

15 Balas, Shimon, 1978. Arabic Literature in the Shadow of War, Am Oved, Tel Aviv, pp. 33-35 (Hebrew).

17 Abdi’s drawings appear in Emile Habibi, 1974: Al-Waka’i al gharieba fi ikhtifa Saeed Abu an-Nash al-Motashel, Jerusalem. Translated into Hebrew without the illustrations: Emile Habibi, 1986. The Secret Life of Saeed, the Pessoptimist (trans. Anton Shammas), Mifras, Jerusalem.

18 A similar image of a corpse recurs in Abdi’s work and in it Käthe Kollwitz’s influence can be seen. Thus, for example, in the last print in the “Weavers Revolt” cycle (1897) (no. 26) Kollwitz depicts two men bearing a corpse into a room of a hut in which the bodies of two workers are already laid out.

19 A previous version of the following appeared in the exhibition catalogue, “Abed Abdi: ‘Wa Ma Nasina’”, of which I was curator in 2008 at Abed Abdi’s studio in Haifa; see the exhibition website http://wa-ma-nasina.com/index.html

21 Khalidi, Walid, 1992, All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948, Washington.

25 In 1996 Abdi returned to this illustration and created “Leaving Haifa” in which he used his father as an updated model. His father passed away a year later.

26 Abdi, Deeb, 1991. Thoughts of Time, Al-Ittihad, Haifa. First published in Al-Ittihad on 27 April.

30 On the importance of monuments and memorial sites, Israel Gershoni notes that the memorial site is a place of memory of the kind described by Pierre Nora. He says that beyond it being a one-time thing or recycled ritual, commemoration is a dynamic process. However, the concrete act of establishing a memorial site creates “a moment of preservation of collective memory” that from a historical standpoint is defined and distinguished (Gershoni, 2006: 26). With regard to these representations of the past, Moshe Zuckermann notes that the ‘one-timeness’ of a historical event is absolute and cannot be resurrected. Accordingly, representation of a historical event is a substitute whereby consciousness of the present attempts to penetrate that of the past. According to him, these representations and motifs act as codes: they contain the coded details of the collective consciousness, but at the same time they serve as a connecting link with those elements excluded from consciousness and stored in memory (Zuckermann, 1993: 6-7). For further reading, see Israel Gershoni, 2006. Pyramid for the Nation: Memory, Commemoration and Nationalism in Twentieth Century Egypt, Am Oved, Tel Aviv (Hebrew); Moshe Zuckermann, 1993. Holocaust in the Sealed Room, published by the author, Tel Aviv.

31 Gershon Knispel was born in 1932 in Köln, Germany, and grew up in Haifa. In 1954 he completed his studies at the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem. In the early 1960s he was living in Brazil but returned to Israel in the wake of the military coup that took place in Brazil in 1964. In the 1960s and 70s he was the Haifa Municipality’s artistic advisor. In 1994 Knispel returned to Brazil, to San Paolo, where he lives to this day. His rich artistic ability and experience, coupled with his extensive contacts, which enabled the artists to cast the Land Day monument in the Haifa Municipality’s workshop, made his contribution to the monument’s erection all the more significant. Knispel designed several monuments in the 1970s: the Kfar Galim Youth Village monument (1970), the monument in Haifa’s Ahuza neighborhood (1974), and the one in the Haifa Memorial Garden (1975). See, Esther Levinger, 1993.War Memorials in Israel, Hakibbutz Hameuhad, 31 (Hebrew).

32 The portfolio, graphically designed by Abed Abdi, was published several months after the monument was erected. Apart from the four preliminary sketches, also included in it are photographs taken by the then photographer of Al-Ittihad, Gideon Gitai, and texts by Samih al-Qasim, Joshua Sobol, and the monument’s creators, Abed Abdi and Gershon Knispel.

33 Sorek, Tamir, 2008. “Cautious Commemoration: Localism, Communalism and Nationalism in Palestinian Memorial Monuments in Israel”, in Comparative Studies in Society and History, 50 (2): p. 330.

35 Yael Zerubavel emphasized that commemoration is a central concept in the understanding of the dynamics of change that take place in memory. Collective memory is realized in varied commemoration forums, when by means of these commemorative rituals groups create, amend, rehabilitate and process, through negotiation, their common memories of particular events and seminal moments in accordance with the changing needs of the present. From this standpoint, public commemoration is not only a more accessible site for research of the formation of the collective memory, but it also enables following the changes and reproductions taking place in the collective memory of a specific community over time. See, Zerubavel, Yael, 1995. Recovered Roots: Collective Memory and the Making of Israeli National Tradition, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, pp. 4-13.

36 The woman’s broad, almost Indian-like face and heavy body call to mind the images of women in the monumental murals done by the Mexican artists Diego Rivera (1886-1957) and David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896-1974). Abdi met the latter in Dresden in 1969.

37 Clearly evident here is the influence of Kollwitz’s “The Grieving Parents” (1914-1932), commemorating the artist’s son Peter who fell in World War I (and who lost her grandson in World War II). She spent seventeen years working on the monument commemorating her son, which was unveiled in 1932 in a cemetery in Flanders where her son fell and was buried. The monument shows Peter’s mother (a self-portrait of the artist) and father (a portrait of Karl Kollwitz) kneeling at their son’s side, begging his forgiveness.

38 The figure of the woman in the village as a representation of the Palestinian homeland constitutes a central motif in Palestinian art from the 1950s to the present day. In the context of my research on Palestinian art I contended that this centrality of the woman’s figure in canonical Palestinian art is influenced by and expresses the way in which national movements perceive the roles of gender. See my MA thesis: Tal Ben Zvi, 2004. “Between Nationality and Gender: Representations of the Female Body in Palestinian Women’s Art”, Tel Aviv University. A further discussion of Palestinian women’s art appears in the catalogues: Tal Ben Zvi, 2006. Hagar – Contemporary Palestinian Art, Jaffa: Hagar Association; Tal Ben Zvi, 2006. Biographies: 6 Exhibitions at Hagar Art Gallery, Jaffa: Hagar Association; Tal Ben Zvi and Yael Lerer 2001. Self-Portrait: Palestinian Women’s Arts, Tel Aviv: Andalus.

39 Abdi, Abed, 1978. “Monument to the Present, The Story of a Monument, Land Day in Sakhnin, 1976-1978”, Abed Abdi and Gershon Knispel (eds.), Arabesque, Haifa.

40 Naseer Aruri and Edmund Ghareeb (eds.), Enemy of the Sun: Poetry of Palestinian Resistance, Washington, Drum Press, 1970, p. 66.

42 See Anat Zohar, “It Doesn’t Compliment Me or the State”, at http://bidur.nana10.co.il/Article/?ArticleID=600807