“Wa ma nasaina” (“We have not forgotten”) exhibition is a personal journey in time, memory andhistory of Palestinians, which constituting an integral part of the life of artist Abed Abdi, who was bornin Haifa.

The exhibition contains paintings and lithographies which were published as photographic copies for 20 years, starting at the end of the 1960s, in Al Ittihad newspaper, Al Jadid literary magazine,on the covers of books, and as illustrations inside books.

Among the books in which these illustrations were published are Emile Habibi’s two books, “Sextet of Six Days” (1968) and “The Pessoptimist: The Secret Life of Saeed Abo el-Nahs al-Motashel” (1977), Salman Natour’s “Wa ma nasina” (We Have not Forgotten) (1982), Felicia Langer’s “With My Own Eyes” (1974), Joseph Algazi’s (Galili) “Father, What Did You Do When They Demolished Nader’s House?” (1974), as well as Moshe Barzilai’s anthologies of poems.

Abed Abdi was born in Haifa in 1942, in the Church Quarter in the Lower City. In April 1948 he was uprooted from his home, together with his mother, his brother and his sisters, while his father remained in Haifa. From Haifa they went to Acre, seeking protection within the town walls. Two weeks later, they left to Beirut on a rickety boat, coming at first to the “Karentina” transitional camp in the Beirut harbor, and later on to the refugee camp “Mia Mia” near Sidon, from which they later on moved to Damascus. For three years, Abdi, as a child, was moved from one refugee camp to another, lacking any framework and with no connection with his father. In 1951, Abdi and his family members were allowed to return to Israel, as part of a family reunion.

As an adolescent, Abdi joined the Communist Youth Alliance in Haifa. This is also where his artistic road began. He met the artists of Social Realism, whose representative in Israeli art are Ruth Schloss, Shimon Zabar, Naphtali Bezem, Moshe Gat, Gershon Knispel and others. In 1962, Abdi was accepted into the Haifa Association of Painters and Sculptures, the first Arab artist to become member of this association. In 1964 he went to study art is Dresden, in East Germany, through a scholarship that he received from the Communist Party in Haifa. In Dresden, he met Lea Grundig (German, 1906-1977), a Jewish artist who is identified with protest illustrationes against Fascism and Nazism. He remained in Germany as a student for eight years, in the course of which he met his wife Judith, a student from Hungary who had also come to Germany to study. Their common language is German; with their three children they speak Arabic, German and Hungarian.

Abdi returned to Israel in 1971. In the course of the years he presented his works in a large number of solo and group exhibitions. In 1978, he created and built, together with Gershon Knispel, the Monument commemorating Land’s Day in Sakhneen2, and later on he created other monuments in Shfra’am, Kafr Kana and Kafr Manda. In the course of the years he also worked as a drawing teacher in Kafr Yasif and as an art lecturer in the Arab College of Education in Haifa. In the years 1972 to 1982 he was the graphic editor of the newspaper Al Ittihad and of the literary journal Al Jadid. For ten years he affected the visual culture of the Palestinian minority in Israel, with many of his illustrationes appearing regularly in the daily newspapers, in journals and in books, as well as on many posters, including Land’s Day posters, posters commemorating the Kafr Kassem Massacre and election posters for the Israeli communist party (MAKI).

This brief biography emphasizes the centrality of the art of print in Abdi’s creation. This art of print continues the art of print in canon Palestinian art, which began in the sixties, with the posters of Ismail Shammut, which were distributed in the refugee camps of Beirut, and continued mainly in the eighties, with posters and calendars by Suleiman Mansour and others, which were distributed in the Western Bank and Gazza, especially during the time of the First Intifada in 1987.3

The name of the exhibition Wa ma nasina (We have not forgotten) is the same as the title of Salman Natour’s popular book, which contains a number of short stories about the occurrences of the Nakba in the year 1948. These short stories were first published in Al Jadid, in the years 1980-1982. Every story in the magazine began with an illustration by Abdi, where the title is featured as part of the illustration.4

The name of the exhibition Wa ma nasina (We have not forgotten) is the same as the title of Salman Natour’s popular book, which contains a number of short stories about the occurrences of the Nakba in the year 1948. These short stories were first published in Al Jadid, in the years 1980-1982. Every story in the magazine began with an illustration by Abdi, where the title is featured as part of the illustration.4

The titles of the stories are: So We Don’t Forget, So We Shall Struggle: Introduction by Dr.Emil Tuma; A Beating Town in the Heart; “Discothèque” In the Mosque of Ein Hod; Om Al Zinat is looking for the Shoshari; “Hadatha” who listens, who knows?; Hosha and Al Kasayer; Standing at the Hawthorn in Jalama; A Night at Illut; “Like this Cactus” in Eilabun; Death Road from al-Birwa to Majd al-Kurum; Trap in Khobbeizeh; The Swamp… in Marj Ibn Amer; What is Left of Haifa; The Notebook; Being Small at Al-Ain… Growing Up in Lod; From the Well to the Mosque of Ramla; Three Faces of a City Called Jaffa.

The names of the stories reflect a remapping of mandatory Palestine, the lost Palestine. This is similar to the well-known story of the historian Walid Khalidi, “All That Remains”, which documents the 418 destroyed Palestinian villages5.

Unlike the format of the short stories in Al Jadid, in which a different illustration by Abdi appeared in each story, only two illustrationes were chosen for Salman Natour’s book, and they create the space of the Palestinian memory. On the cover of the book appears a illustration that originated in the story “Being Small at Al-Ain… Growing Up in Lod”6, in which two female figures are presented, refugee women with their eyes downcast, their headdress and heavy dresses turning them into a kind of single monumental figure against the background of a blurred architectural structure.

“We have not forgotten”, says the headline of the book, with the illustration indicating a consciousness of memory – abstract memory that is not located in a concrete geographic space.

The second illustration was originally published as part of the story “What is Left of Haifa”7, and it is a detailed illustration of the City of Haifa. The headline of this illustration, “22nd April 1948”, constitutes a biographic and collective indication of the date in which Arabs were deported from Haifa; a historical moment, anchored in time and place.This illustration is reproduced and recurs besides every headline of every short story in this book. The illustration becomes a logo, and links Abdi’s personal biography as a native of Haifa with the sequence of story names. From Haifa to Lod, From Haifa to Ramle, From Haifa to Jaffa, etc. A space of geographic memory, names of places, details of streets, businesses and the names of people on the time axis of the Palestinian Nakba.

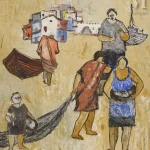

This illustration is “The Father Illustration”, an illustration that contains the essence of the iconography that accompanies Abdi’s creation in the course of the years. The illustration is composed as a Triptych: in the left section, a large number of figures are sketched as black patches, becoming a human swarm that seeks to leave from the Port of Haifa with great density and congestion. In the central part there is the figure of the father, Kassem Abdi, with a simple worker’s hat on his head, and behind him the “Kharat Al Kanais” (“Church Neighborhood”, with its churches, mosque and clock tower, as well as the family home. In the right section of the illustration, there is a graphic sketch of the ruins of the Old City.

Later on in this page, under the illustration, Natour describes, in his story:

The age scared man that we speak of, walks hand in hand with the years of this century […] “The Nakbeh”, he says: “I was 48” and adds: “I witnessed it at the day when their cannon was on the bridge, and they dropped a bomb full of yellow on the clock near the Jarini mosque, so the clock fell, and I said: the clock fell, and the homeland will follow. Haifa was not erased from the face of the country, but it has changed tremendously […] how can we write everything about Haifa? So we wrote a little of the little, of that which the age scared man was able to impart to us. The ruins of the Jarini mosque or the Basha’s baths upon which pieces of glass would glitter at dawn to play tricks of light on the marble statue of Faisal.

“The people of old Haifa were mostly fishermen and stone workers. They used to take the stones from Wadi Rushmia and sell them. And when the British came and expanded the harbor, we started to work there as well. Rifaat, was a honed fisherman, he had a black donkey which he used to stand upon and look to the sea, and see where the fish gather, then he would throw in his net, and not miss even a single fish. Time passes by, and the sea began to bring people and to send people away. And Abu Zeid’s boats took the Arabs away… Where to?

To Acre

To Beirut

To Sidon

Where? To the bloody hell…”( Natour, 1982) 8

Salman Natour’s story about Haifa is based, to a great extent, on the stories of Abdi’s family. Thus, for instance, Rif’at the fisherman is the uncle of Abdi’s father. The story of the family, in detail, appears in the book written by Deeb Abdi (Abed Abdi’s brother), “The Thoughts of Time”, which was published in 1993, after his death. In the book, short stories that he had written and which had been published through the years in Al Ittihad were collected, including the story of the family’s grandfather and his departure from Haifa in April 1948.

Salman Natour’s story about Haifa is based, to a great extent, on the stories of Abdi’s family. Thus, for instance, Rif’at the fisherman is the uncle of Abdi’s father. The story of the family, in detail, appears in the book written by Deeb Abdi (Abed Abdi’s brother), “The Thoughts of Time”, which was published in 1993, after his death. In the book, short stories that he had written and which had been published through the years in Al Ittihad were collected, including the story of the family’s grandfather and his departure from Haifa in April 1948.

The illustration on the cover of the book is also related to the departure from the City of Haifa. The images in this illustration are arranged in the composition of a cross, so that the horizontal line is formed from the houses of Haifa, sketched in black and outlined by the waterline of the Port of Haifa, while the vertical line is formed out of a fishermen’s boat, with heavily outlined figures on it in black lines. The three figures at the front of the illustration are in detail: the figure of a woman holding a kind of package close to her body, the figure of an older man and beside him, the figure of a young child, leaning against the side of the boat.

“I was hearing these conversations and living them, when adults uttered them in front of the children, so I become more afraid, afraid of darkness, it frightened me to death, afraid of darkness, of the unknown, until the Disaster occured, and I had to leave Haifa for Acre, in British armored vehicles.

In April, the sea was stormy, which is unusual at that time of the year, and the high tide almost took us to the deep waters, deeper and deeper to the bottom of the sea. My grandfather Abed el-Rahim was standing upright as if he was challenging the waves and other things; he was looking back at Haifa, as if they were saying goodbye to each other. For the first time he was leaving Haifa, and she was leaving him, and she faded away bit by bit, and my grandfather Abed el-Rahim watched the length of the shore from Haifa to Acre, the wheels of a carriage pulled by horses, bogging down in the

moist sand. A short trip, then we go back. That is what my grandfather Abed el-Rahim said when I was still a little boy, hardly eight, and I was afraid of darkness, of the sea, for the first time in my life, sailing to an unknown world – unknown.

From the great mill, they were shooting bullets like heavy rain, and my grandmother Fatim el-Qala’awi hid us in her lap, continuously reciting the Throne Verse, and we did not dare raise our heads, so we remained as we were, until we came on a wide distance from the shore to the deep sea, and came very close to Acre. In Acre we stayed for couple of weeks. The walls of Acre were suffocated by migrates, and the migrates were suffocated by crowds of immigrants who hurried up inside the walls, through land and sea. After a short time, Acre fell, and the departure was through land and sea. We went on board at night, and sailed deep to the world of exile, from Haifa to Acre. It was the beginning of traveling… and traveling… and traveling.

(2) The beginning of the return

I am tired of traveling, wandering from one country to another. My grandmother Fatima died of sorrow in Bilad al-Sham (Syria), and my grandfather Abed el-Rahim passed away in the Mia Mia Camp, far away from his beloved Haifa, the city that he loved more than love itself. Haifa and my grandfather are twins, she was a piece of him, and he could not bear the departure. Before he passed away, he gave us his legacy: to return to Haifa, and never leave it no matter what happens. He wished to be buried in Haifa in the upper cemetery, right next to Al-Istiqlal Mosque, among his relatives and loved ones. (Deeb Abdi, 1991).9

In the story, the grandmother takes everyone into her lap, with the story being told by a child who is afraid of the dark and of the sea, and is waiting for a savior to save him of his misery. The expectation for a savior, for someone to save him from drowning in the sea, is familiar to Abdi from his mother’s stories about El-Khader. This figure appears in Salman Natour’s story “What is Left of Haifa”, which has been described here in detail. In the story, a group of people is visiting the Elijah Cave (El Khader). They drink and eat, get a little drunk and when they go into the sea they begin to drown. “The old people began to pray: Please Khader, Save us Khader”, writes Natour, and suddenly they saw a man in a boat in the middle of the sea, but he disappeared like a grain of salt. And of-course nobody drowned.

This figure of El-Khader as Elijah the Prophet, as Mr. Jarias, a lifesaving figure, recurs in many of Abdi’s illustrations. Thus, in an illustration from 1979, a figure is flying with its arms outstretched, as if it is protecting the group of houses underneath it. In another illustration from 1976, a group of refugees is lifting upwards a kind of “Messiah” figure with his arms stretched above them. The figure of El-Khader, or the figure of the old man, cannot forever protect and save the Palestinian figures the Abdi depicts in his creations. The fact that the protecting figure is almost always flying in the sky, detached from its land and from the source of its strength, points at the limitations of its power and at its location both in the religious and in the community mythology.

The figure of the old man, the Sheik with his lined face, appears as a recurring motive in all of Natour’s Wa ma nasina stories, and in most of the illustrations that accompanied these stories in Al Jadid. However, there is a structured tension between the text, which is based on the figure of the Sheik as the storyteller, who remembers in detail all the events of the Nakba (names of people, dates and places), and the universality of the illustration, as it is manifested in the face of the old many himself and in the faces of the other figures in the illustration series. Thus, for instance, in the illustration that opens the story “From the Well to the Mosque of Ramla”10, the figure of the old man appears, his face deeply lined and with an expression of sorrow, and he is stretching his arms out in the composition of a cross, part exposing himself as a victim and part protecting the figures of the wailing women who are standing behind him with a dead body lying beside them, wrapped in shrouds, on wooden boards.

The figure of the old man, the Sheik with his lined face, appears as a recurring motive in all of Natour’s Wa ma nasina stories, and in most of the illustrations that accompanied these stories in Al Jadid. However, there is a structured tension between the text, which is based on the figure of the Sheik as the storyteller, who remembers in detail all the events of the Nakba (names of people, dates and places), and the universality of the illustration, as it is manifested in the face of the old many himself and in the faces of the other figures in the illustration series. Thus, for instance, in the illustration that opens the story “From the Well to the Mosque of Ramla”10, the figure of the old man appears, his face deeply lined and with an expression of sorrow, and he is stretching his arms out in the composition of a cross, part exposing himself as a victim and part protecting the figures of the wailing women who are standing behind him with a dead body lying beside them, wrapped in shrouds, on wooden boards.

Underneath the illustration, Natour describes in detail a story of slaughter and destruction. In March 1948, tells the storytelling “Sheik with the lined face”, a bomb exploded in the center of Ramla, on market-day Wednesday, causing chaos and the death of many people, with a large number of dead bodies lying among the market stalls and the banana and orange crates.

The tension between the text, which describes violence and loss, and the horizontal composition of the illustration, the black, heavy figures and the location of the illustration in an abstract geographic space that is marked only by the outline of mosque minaret – all these load the illustration with a timeless symbolic system. The lying body, with its face hidden, is simultaneously a specific and a universal victim.

In other illustrations, the dialectics between the detailed text and the nature of the symbolic illustration recurs. An example of this is the illustration that accompanies the story “Like this Cactus” in Eilabun”11. The illustration depicts a figure who is lying injured on the ground, and the figure of a woman who is touching the injured person’s face with a hesitating hand.

Behind them, several woman figures are holding their heads in sorrow. The figures are located in a space that is empty of other human beings, far from any place of dwelling and from any source of help.

Behind them, several woman figures are holding their heads in sorrow. The figures are located in a space that is empty of other human beings, far from any place of dwelling and from any source of help.

The story opens with a long scene in which Natour describes the path out of Eilabun, the fields and the mountains all around, and the tension between a young Palestinian woman and her children and an Israeli soldier who is with them on a truck going from Eilabun to Tiberias.

Later on, the storyteller tells of the massacre in Eilabun, the death of Azar, a poor man, the children’s favorite, who was killed while leaning against the church door, and the death of Sama’an al-Shufani, the janitor of the Maroon Church, whose body remained on the ground for three days.12

In the illustration that appears at the beginning of this story and in many additional illustrations in the Wa ma nasina series, the figures are located in an abstract geographical space, which is sometimes graphically outlined in a small number of lines. The figures are placed on the white paper, and they draw their local, concrete strength from the literary textual space. Kamal Boullata describes this textual influence of the Arab literature, poetry and spoken language on Palestinian art as “hidden connotations of the words”, which have become the hidden components of Palestinian art.13

This textual space includes the rich literary writing of authors and poets such as Emile Habibi, Anton Shammas, Muhammad Ali Taha, Salman Natour, Samih al Qassim and others. A unique connection is evident between Abdi’s illustrations and the literary creation of Emile Habibi, who was also born in Haifa.

Abdi contributed many illustrations to Emile Habibi’s writings. An example of this is an illustration that appears at the end of the story “Mendelbaum Gate”, in Habibi’s book of short stories “Sextet of Six Days” (1968).14 In this illustration, a woman with a lined face appears, holding a black stick, and behind her a figure of a girl-woman, near a barbed wire fence, her body throwing a heavy shade on the figure of the woman. The figures are in an empty space, between past and future, appearing to be fixated, as if they find it difficult to move towards the unknown. The contradiction between the black outlines of the body and the delicate lines that depict the lines on the face emphasizes the rigidity of the figures and their emotional state. Mendelbaum Gate, which defined the border between the two parts of Jerusalem before 1967, was the only passage between Israel and Jordan. Once a year, on Christmas Day, Christians from Israel were allowed to cross this gate in order to visit their relatives in the refugee camps in Jordan. Shimon Ballas notes that this gate, which had symbolized the division of Jerusalem, also symbolized the division of the Palestinian people.15

Balas expands on the way in which Emile Habibi describes the parting from his mother, who was about to join her sons in Jordan.16 Habibi describes Mendelbaum Gate as an empty area, with a forlorn gate at each end, a no man’s land that separates between two worlds: “He who leaves here, will never return”, says the Israeli customs officer to the storyteller.17 But the storyteller did not need this explanation. His mother, too, who wished to live the rest of her life in the Holy City, did not need it, as she was imbued with “awareness of the torn motherland”. But what is the motherland, asks Habibi, is it Nazareth, where she had lived for twenty years of her life, or Jerusalem, the city that she had known when she was young? The motherland is also that no man’s land between the gates, an area that once crossed, becomes like “the valley of death, with no way back”. Balas describes this as a double tear: “Those who have been made to live outside their country hope to return to it, while those who live apart from most of their people hang on to the hope to be reunited with the others”.

This duality, of the Palestinians “on the inside”, the Arabs of 1948, characterizes Abdi’s work and is doubtlessly influenced by Habibi’s creations. An additional example of this is reflected in the series of illustrations that decorate the pages of Emile Habibi’s book “The Pessoptimist: The Secret Life of Saeed Abo el-Nahs al-Motashel” (1974). In the illustration that appears in the beginning of the book there is a close-up of a man whose hand is covering half of his face.

The hand, which hides the facial features (and does not make it possible to identify the author’s face), is turned with its palm to the reader-viewer, who to a certain extent is invited to read the author’s future in his palm.

This is how Abdi depicts the figure of the writer Emile Habibi, who conducts a complex dialogue that is based on hiding and exposing while presenting the complexity of the identity of the Palestinian minority in Israel.

Abdi’s art of print, his illustrations, his stone prints and lithography, were first exposed to the wide public in black and white, printed on a newspaper page, in the textual space of the Arabic language. As a result of the small number of artistic exhibition spaces such as galleries and museums in the Arab society in Israel (especially in the seventies and eighties), as well as the absence of an artistic critical discourse in the Arab newspapers, the Palestinian literary text that appears alongside the illustrations becomes an iconography from which the works of art are interpreted and read.

“Awareness of the torn motherland”, in Habibi’s words, is an appropriate general expression for Abdi’s creation, where Haifa residents, harbor workers, fishermen and land farmers populate his illustrations alongside refugees and displaced people from the other side of the fence. However, this “awareness” strives for universal justice, for universal artistic language that is beyond the borders and the issues of identity and nationality: at the center of his creation, the human figure appears time and time again, sketched in a sensitive illustration that is attentive to the suffering of human beings against the waves of history, the waves of the sea in Haifa, from the viewpoint of a six year old boy, who is torn from his him on a rickety boat in mid-sea.

__________________________________

Notes:

1.Tal Ben Zvi, Currently completing her doctoral thesis at Tel Aviv University on “Representations of the Nakba in Palestinian Art: The Seventies and Eighties in the work of Palestinian Artists who are members of the Palestinian Minority in Israel”. Curator of Heinrich Böll Foundation, Tel Aviv (1998-2001) and Hagar Art Gallery, Jaffa (2001-2003). Select Publications: Hagar – Contemporary Palestinian Art (2006) Jaffa: Hagar Association, Biographies: 6 Exhibitions at Hagar Art Gallery (2006), Jaffa: Hagar Association, “Mother Tongue”, exhibition Catalogue (2004) in Yigal Nizri (ed.), Eastern Appearance / Mother Tongue: A Present that Stirs in the Thickets of Its Arab Past ,Tel Aviv: Babel, Self-Portrait: Palestinian Women’s Arts (2001), Tal Ben Zvi and Yael Lerer (eds.), Tel Aviv: Andalus, and more.

2. The Monument in Sakhneen was at the center of the exhibition: “The Story of a Monument: Land Day in Sakhneen” (curated by Tal Ben-Zvi). Further details of this exhibition: Gish Amit, 2008. “You Will Build and We Will Destroy: Art as a Rescue Excavation”, Sedek 2 Journal, pg. 117-119

[Hebrew]. And in the Hagar Gellery Site: www.hagar-gallery.com

3. For further details, see: Tina Sherwell, 2001. “Imagining Palestine as the Motherland,” in Tal Ben Zvi and Yael Lerer (eds.), Self Portrait: Palestinian Women’s Art, Tel Aviv: Andalus; Kamal Boullata, 2001. “The World, the Self, and the Body: Pioneering Women in Palestinian Art,” in Tal Ben Zvi and

Yael Lerer (eds.), Self Portrait: Palestinian Women’s Art, Tel Aviv: Andalus; Kamal Boullata, 2000.”Istihdar al- Macan: Dirasat fi al-Fan al-Tashkili al- Filastini al-Muasir” (The Recovery of Place: A Study of Palestinian Contemporary Painting), Tunis, ALECSO.

4. In 2007 it was published again in a different format, as part of the author’s trilogy on the Palestinian memory, called “Memory” and published by the “Bdil” Organization in Bethlehem.

5. Walid Khalidi, 1992. All That Remains. The Palestinian villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington 6 Salman Natour, October 1981. “Being Small at Al-Ain… Growing Up in Lod”, Wa ma nasina (We have not forgotten), Al-Jadid [Arabic].

7. Salman Natour, December 1980. “What is left of Haifa”, Wa ma nasina (We have not forgotten), Al-Jadid [Arabic].

8. The story “What is Left of Haifa” Wa ma nasina, in Hebrew and in English, was published in the book “Remembering Haifa”, Published by the “Remembering Association, Site: http://www.zochrot.org/index.php?id=511

9. Deeb Abdi, first published in the Al Ittihad newspaper, 27 April 1991 [Arabic].

10. Salman Natour, November 1981. “From the Well until the Mosque of Ramla”, Wa ma nasina (We have not forgotten), Al-Jadid [Arabic].

11. Salman Natour, March 1981. “Like this Cactus in Eilabun”, Wa ma nasina (We have not forgotten), Al-Jadid [Arabic].

12. Benny Morris notes that the Village of Eilabun, most of whose residents were Maroon Christians, was occupied on the 30th of October 1948 by units of the “Golany” Brigade. The residents gathered inside the churches, and the priests declared that village had surrendered. But when the soldiers went

around the village they found, in one of the houses, the severed heads of two Israeli soldiers. The residents of Eilabun were ordered to gather in the village square, where one of the village people was shot to death and another wounded. Later on, the commander chosen 12 young men, who were killed in the streets of the village. The village residents (800 in number), women and children, were marched in their sleeping clothes and without any food to El-Ma’er, with the army cars driving behind them. When they came to Anan Village, an armored vehicle fired at them, and as result, an old man

Sama’an al-Shufani – was killed, and three women were wounded. The soldiers stole 500 Israeli liras from the villagers, and gold jewels from the women, and sent 42 young men to a detention camp. They others were led the following day to Meiron, and from there to the Lebanese border. After the

residents were exiled, the soldiers raided and plundered their houses. In the summer of 1949, the Eilabun exiles were allowed to return to their village. For further details, see: Benny Morris, 1987. The birth of the Palestinian refugee problem, 1947-1949, Cambridge University Press

13. Kamal Boullata, “Israeli and Palestinian Artists: Facing the Forests,” Kav,10 (July 1990), pp. 170-175 [Hebrew].

14. “Mendelbaum Gate” was first published in Al-Jadid, in March 1954. It is included in Emile Habibi’s book Sextet of The Six Days, 1970 [1954], Haifa [Arabic].

15. For further details, see Shimon Ballas, 1978. Arab Literature under the Shadow of war, Am Oved Publishers, Tel Aviv [Hebrew].

16.Ibid.

17. Emile Habibi, 1970 [1954]. “Mendelbaum Gate”, Sextet of The Six Days, Haifa [Arabic].

___________________________

download this review (pdf, 14 pages, English, including images). Also, please visit the exhibition “Wa ma nasina” online here.

Curator: Tal Ben Zvi

you may want to read the short stories by Palestinian writer Salman Natour, titled “Wa ma nasina” (We have not forgotten), published in Al-Jadid between 1980-1982. These stories provide the bagkround to some of the illlustrations presented there, stories describing the Palestinian Nakba.